Thanet Parkway station opened on 31 July 2023, and promptly broke quite a few people’s brains. I can remember my Twitter feed (as was) being awash with commentators deriding its appearance. Even now, a simple web search will quickly turn up adjectives like “ugly”, “hideous”, “bloody ugly” and “incredibly dull-looking”.

Although I assume the post must have been deleted as I can no longer find it, someone even went so far as to sketch out a Victorianised version of the station with decorative ironwork and Gothic Revival fiddly bits added, although your feelings about whether this would necessarily be an improvement would be related to your wider feelings about buildings pretending to be of an age they aren’t. Looking at you, National Gallery Sainsbury Wing.

The rationale for Thanet Parkway has been called into question, with residents and commentators saying it “seems pointless” or is “a waste of public money.” (I’m not linking directly to these – I don’t want to start a pile-on.)

But can the station really be all that bad? I think not, but before we start, a warning. I fully expect you to disagree with this article. I’ve tried to convince various people of Thanet Parkway’s merits, with very limited success. Nevertheless, I am here to tell you that Thanet Parkway is not as bad as you’ve been told. And it’s probably about right for what it actually is.

The thing about Thanet Parkway is that the whole controversy over its appearance is based on a category error. Because really, Thanet Parkway isn’t a station at all.

Let me take you back to the days of the railway’s ‘golden era’ of the early 20th Century. Back then, there were different sorts of railway stations, with different names: stations, platforms, and halts. Stations with a geographic name only were proper stations, while the ones which had ‘Halt’ or ‘Platform’ as a suffix were something different.

This was a fairly helpful distinction, because in the days before DfT station categorisation (which still isn’t easily available to the travelling public in any case) the inclusion or exclusion of ‘Halt’ or ‘Platform’ from a station name gave travellers a sense of what to expect from it in terms of passenger facilities, and indeed its general appearance.

Stations had staff, and almost certainly a substantial, enclosed waiting room. You could also deposit goods at a station for onward transport, thanks to the common carrier obligation placed on the railways. Platforms (the rarest of the three) had, if I understand it correctly, minimal staffing and didn’t accept goods. Halts were unstaffed, had no facilities for goods, and the best you might expect in terms of waiting accommodation was a non-fully enclosed shelter and, at many halts, not even that. Certainly you would not expect to find an actual station building, and the shelters were usually basic and with limited attention given to their aesthetic appeal.

Read your railway history and you will encounter at some point the GWR’s ‘pagoda’ shelters which graced many a halt, but to be honest giving them a fancy name doesn’t make up for the fact that they were basically tin shacks.

Photo by Geof Sheppard, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As always with the railways, the reality was never quite as simple as the above explanation suggests, and some halts actually did have proper (if diminutive) buildings. For instance, Lydd-on-Sea retained a tiny station building from its previous existence as an actual station, when in 1954 it was downgraded to halt status and renamed Lydd-on-Sea Halt.

The suffix “Halt” was largely dropped from station names by British Railways during the 1970s, not least because BR’s widespread rationalisation and de-staffing scheme for stations at the time was threatening to cause some surprisingly large stations to have to be renamed ‘halts’ (that’s the urban legend, anyway).

The last halt was IBM Halt in Inverclyde, which lost its suffix as late as 1983. Unfortunately you cannot visit this historic location because since 2018 it has been closed. In unsurprising fashion for the British rail industry, although it is closed it is also not actually closed because of all the legal trouble that would attend such a status were it to be formalised. As station operator ScotRail puts it, “Trains no longer call at this station until further notice.” Which sounds closed to me. Even though it isn’t.

Today there are two stations on the national rail network which include the ‘halt’ suffix. St Keyne Wishing Well Halt and Coombe Junction Halt in Cornwall have been called ‘Halt’ on their signage since 2008 but not (as far as I can tell) in the official railway industry databases. They might not be official halts at all then, although the fact that they are called halts is rather charming for users and does give an accurate sense of the facilities available at each.

And that lengthy diversion brings us back to Thanet Parkway. Because Thanet Parkway isn’t a station… it’s a halt. It is unstaffed, and was only ever intended to have minimal waiting facilities, like many other park and ride stations, as we have discussed before. After all, if you’re expected to turn up to a park and ride station in a car, you are already in something that acts as your own private waiting room. What bus and bike users are supposed to do in such circumstances is anyone’s guess, although some park and ride stations don’t have buses in the first place (Thanet Parkway included), and British utility cyclists are well accustomed to being completely overlooked as part of the transport mix anyway1.

Were Thanet Parkway to be called Thanet Parkway Halt, and were small, unstaffed stations still suffixed ‘Halt’ as a matter of course, people would have had fewer expectations about its appearance, and would perhaps have been less disappointed/shocked/infuriated when it opened looking as it did. They might in fact have expected it to look fairly basic, just as halts always did when they were actually named as such.

Frankly, even getting Thanet Parkway to the point where people were disappointed with its appearance was a bit of a slog, but it was a not atypical example of the way even fairly small scale British transport projects go through endless public consultations, resultant delays, shocking cost increases, funding crises and so on. Strap in…

After earlier developer-led proposals for a station to serve 800 new homes and link with nearby Manston Airport via a shuttle bus link, Thanet Parkway arguably started as a serious project in July 2014, when the government awarded funding for the station, then costed at £10m (remember that number). Promoted by Kent County Council, Thanet Parkway was in a slightly different location from the earlier developer-led proposition, but like its forerunner it was designed to serve new housing developments, as well as providing a convenient new location for car drivers to access the railway network, rather than driving into Ramsgate. It was no longer intended as a rail-air interchange for Manston Airport though, because the airport had closed two months earlier.

Still, it’s an ill wind that blows no-one any good, and the airport has been repurposed as an emergency lorry park to cope with post-Brexit delays at the Britain/France border. It might reopen in 2028, but Britain doesn’t exactly have the best record on transport project delivery at the moment, so I’d be cautious about putting the date too firmly into your diary.

Artist’s impressions of Thanet Parkway have been knocking around since 2015, when the first public consultation into the station project saw the proposed design looking like this.

Some design features to note here are the all-white finish, low height fences at the back of the elevated platforms, the overhanging roofs to the tall lift towers, and a footbridge span above the platforms, linking them to the main entrance. Also the awe-inspiring public realm in front of the station. By this time the station was priced at £14m. It would not be the final occasion on which the cost of the new station crept upwards.

Indeed, by 2016 the estimated cost of the station had already risen an impressive 185% from the 2015 estimate to £26m. It was at that time being opposed by Ian Driver, a former Green councillor on Thanet Council who described Thanet Parkway as “a massive white elephant”, perhaps confusing the white footbridge and lift towers for an actual member of the order Proboscidea.

Although opposing a new railway station might seem a curious position for a former Green councillor to take, it was at least consistent with the British Green Party’s frequent if puzzling opposition to new railway infrastructure. For years it opposed HS2, until it finally reversed that position in 2024, but conveniently only after then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had already cancelled all the bits of it not already under construction.

2017 saw a second Thanet Parkway public consultation by Kent County Council. The station was now shown with sand-coloured lift towers rather than white, and a glass-clad footbridge span, with the glass wrapping around the upper parts of the lift towers.

At the backs of the platforms, full height glazed walls were now proposed. This was almost certainly an inevitable design change, as I can’t imagine the Office of Rail and Road signing off on the low height fences originally suggested, given the risks of someone falling/jumping over them and plummeting down the embankment to serious injury or worse. The new glass walls would also act as acoustic barriers, which would have helped sell the project to sceptical locals – the British public having a peculiar idea that railways are particularly noisy, maybe confusing them with roads, with which they tend to be more familiar.

A third public consultation (and you wonder why every piece of significant national infrastructure takes so long to build in Britain) in 2018 resulted in feedback that the footbridge over the platforms was “considered to have a significant negative visual impact.” Reader, I have been to Thanet Parkway, and I am not sure exactly what the footbridge would have visually impacted on. Again, in a very British way, it feels a bit like objecting to the visual impact of a wind turbine… located in front of a gargantuan oil refinery.

The footbridge was nevertheless deleted as a result, and a decision made to re-use an existing arch under the track as a subway between the platforms. Kent County Council added that, “…once refurbished as part of the scheme [this] will also improve the existing Public Right of Way and bring an old piece of Victorian railway infrastructure (Petley’s Arch) back to life and improve the public realm.” That seems like some mighty post-hoc justification, given that nobody had previously suggested the Victorian railway infrastructure in question needed bringing back to life, nor indeed even noticed it.

In 2019, a fourth public consultation (this is a two-platform, unstaffed halt we’re talking about here, remember) showed a visualisation of the station more-or-less as finally built, without footbridge, with plain tops on the lift towers (no overhanging roofs), and the acoustic barriers changed from glass to solid metal. It is not entirely clear why this last change was made, and it would later prove to have significant impacts on people’s perception of the station, with the platforms once memorably described as “a mugger’s paradise.” I suspect a number of factors converged to lead to the decision.

Firstly, not only do British people (or rather, the sort of NIMBY British people who respond to public consultations on railway infrastructure design) think trains are noisy and need to be placed behind noise barriers, but they would also largely prefer not to see the trains either. That is why large parts of whatever is left of HS2 will be hidden in unnecessary (and costly) tunnels and cuttings, or behind acoustic barriers. It is also why the elegant design of HS2’s Colne Valley viaduct has been compromised by the installation of barriers either 1.65m or 4m tall along its length. Although some of the 4-metre barriers have transparent sections along the top, the rest are opaque, as are the 1.65m barriers. This means HS2 trains will for the most part be neither seen nor heard, while passengers on HS2 trains traversing the viaduct will find their view out significantly comprised. For comparison, HS1’s Medway viaduct doesn’t have 4-metre noise/sight barriers protecting it and the apocalypse hasn’t yet arrived in north Kent.

Secondly, with Thanet Parkway’s projected cost increasing alarmingly – by the time of the fourth public consultation it stood at £34m – there was clearly a degree of value engineering (a.k.a. cost-cutting) going on.

Thirdly, large parts of the public sector in Britain have become enamoured with performatively delivering minimum viable projects to head off manufactured outrage from loony right wing pressure groups like the TaxPayers’ Alliance and their friends in the populist media. By delivering projects which actively look cheap and nasty, public bodies can demonstrate that they are spending the absolute minimum they need to. It’s why a lot of publicly-funded infrastructure is so grim and uninspiring at the moment. There are happy exceptions to the rule, of course. Transport for London, for instance, is still building small railway stations of exceptionally high quality, like Hackney Wick.

In terms of Thanet Parkway, it might have been in the back of the minds of some of the station’s promoters that an ugly steel wall had the advantage of looking cheaper and nastier than a glass one, helping to ‘prove’ that the rising cost estimates of the station weren’t due to wasteful spending on fripperies. As a later Kent County Council report put it, “The design focused on providing basic facilities and no additional benefits.” Like being able to see out of the station once you’re on the platform, I suppose.

An increased government contribution of £12m towards the station’s cost was announced in 2020 and construction finally began in 2021, the Covid pandemic having thrown a further spanner in the works in the form of increased costs for just about everything, and the simple difficulty of getting anything built when no-one was supposed to be within two metres of anyone else. Ongoing post-pandemic general increases in material costs resulted in the the Thanet Parkway project being granted a further £0.88m in 2022.

The station finally opened in July 2023, around nine years after the project properly got started. Noting that the station had been, “…a long time in the making,” (well, indeed) Network Rail Kent route director David Davidson added, “We are committed to encouraging as many people as possible to ditch the car and use the train as their preferred method of travelling,” which was an interesting way of putting it given that the very point of a parkway station is that passengers are generally expected to access it by… car.

The final cost of the station is surprisingly hard to state with any certainty. Normally scheme promoters are only too happy to trumpet the amount of local investment such a station represents, but everyone seemed to be a bit embarrassed by the cost of Thanet Parkway, certainly compared to the initial budget estimates of £10m. Kent County Council said the final cost was £39.3m but noted that there were future liabilities associated with the project. Others suggested the final cost was closer to £44m. The list of funding sources, again not particularly well publicised but detailed here against Kent County Council’s £39.3m figure, was:

- Local Growth Fund (LGF) £14,000,000

- Kent County Council (KCC) £7,078,408

- Thanet District Council (TDC) £2,000,000

- New Stations Fund 3 (NSF3) £3,400,000

- Getting Building Fund (GBF) £12,874,000

Kent County councillor Barry Lewis subsequently picked up Ian Driver’s elephant baton, calling it “a humungous [an inflationary upgrade from Driver’s “massive”] white elephant“. But whatever your feelings about parkway stations and their encouragement of car driving, the numbers speak for themselves. Between July 2023 and March 2024, 57,000 entries and exits were recorded at Thanet Parkway. By the station’s first birthday, 91,000 journeys had been made to or from the station.

Grudging acknowledgement of the station’s utility has been reported by the local press, with comments ranging from, “Amazing … makes getting to London a lot easier with the car park and access,” to, “it’s handy for the adjacent new town development,” via the slightly more qualified, “Not the prettiest of places but does what it’s supposed to.”

So after the slightly extraordinary story of how a two-platform halt station took nine years to build (that’s 1.29 Apollo moon landing programmes, the standard measure for Doing Big Stuff) and cost about four times as much as expected, let’s look at what we got and why it isn’t actually as bad as lots of people think (and will probably continue to think, despite the following).

Firstly, yes, it is an unusual looking station. To the best of my knowledge the architect remains anonymous – and I don’t blame them given the negative attention on the station’s appearance – but I think they’ve not done badly to create a fully accessible unstaffed station, with platforms squeezed onto a narrow embankment.

It is the lift towers which contribute most to the station’s unusual aesthetics (or homely charm if you prefer). Once you know that early iterations of the station design had them extending upwards to a footbridge over the platforms, their slightly stumpy proportions make a lot more sense. They look as though they have been pruned from their original height because they have been.

The material choices for the lift towers and staircase walls are nevertheless quite interesting to see in person, and are not always easy to appreciate from photos. The blockwork comes in two shades of pink and with two finishes (fair and rough).

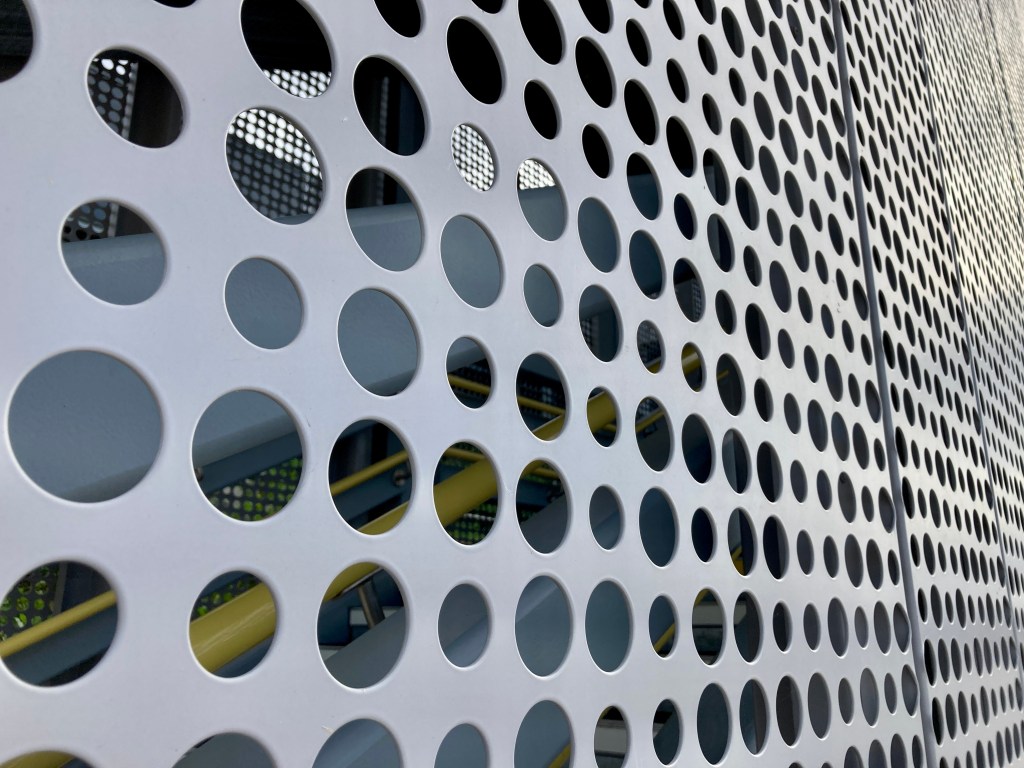

The metal panels around the stairs and lift towers are perforated in an apparently random pattern of large and small circles. But… has anyone run the pattern through a program to decode binary? What if the small circles are zeroes and the large circles are ones (or vice versa)? It wouldn’t be the first time a recent British station contained a mathematical device on its cladding. I like them.

The staircases behind the panels, meanwhile, have a certain industrial panache to them. They also contain these clever tactile signs, built into the handrails.

They are standard on new-build railway stations, but Thanet Parkway was the first time I encountered them.

Its platforms aren’t hugely spacious but experienced in person they certainly feel wider than they look in photos and seem fine to walk along. I don’t have a sense of what they would be like if I were using a wheelchair or had a pushchair; I don’t have that lived experience. I think the tactile guidance strips (which are a welcome inclusion) give the illusion of narrowness to the platforms in photos, by breaking up the area behind the ‘stand behind’ yellow line.

The platform environment is definitely not helped by the non-transparent acoustic barriers which run the full length of the back of the platforms. The single most deleterious change to the station’s design during its lengthy consultation and refinement process was dropping the original transparent panels in favour of these. I can see why people might be concerned about feeling isolated and/or unsafe on the platforms. The station was already substantially over its projected budget by the time it was being built – I would have gone for broke and installed the transparent fencing anyway. The possible reasons why it wasn’t were discussed earlier.

↓ Station heritage plaque commemorating both the opening of the new station, and the long closed Ebbsfleet and Cliffsend Halt, which stood just to the west

Both Photos by Daniel Wright [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

In the Victorian arch which has been repurposed as a subway between the platforms, the station already has some charming individual local character – a school art project, history boards and a railway history plaque have been installed.

The soft landscaping in the car park will grow in and look better over time. And there are flower planters to brighten the place up in the shorter term.

Sometimes, new railway stations feel short of places to sit and rest. Not Thanet Parkway, which has a suprisingly large number of benches, in a surprising variety of designs. The one above, with the little table attached, I particularly like.

There are some unfortunates around, admittedly.

What is this electrical cabinet plonked here for? Couldn’t somewhere less obstructive have been found for it? The litter bins too seem chaotically placed, and are occasionally located directly on pedestrian desire lines.

The two signs above are doing effectively the same thing, and stand right next to each other. This creates visual and physical clutter and only the one on the left is actually necessary.

I wish that the station signage had followed the standards in Network Rail’s Wayfinding design manual, which was already published when Thanet Parkway opened. Instead, Thanet Parkway has a slightly odd hybridised signage system with Rail Alphabet 2 lettering, pictograms from the Network Rail Wayfinding manual, but Southeastern’s signage colour scheme and layout.

When I initially posted my thoughts about Thanet Parkway on social media, someone replied to say that they couldn’t tell whether I was being ironic or not. I really wasn’t. For a very small, very basic station, quite a lot of consideration has gone into its design within the constraints imposed by the site, the type of station it is, and the need to control an inflating budget. There are other recent halt-type stations even more basic than Thanet Parkway which don’t seem to have drawn anything like the same ire. And there are some recently built stations, and I mean proper stations rather than halts, which are far more disappointing in terms of their detailing.

Thanet Parkway though? Not nearly so bad as you’ve been told. ■

- This reminds me – I really must have a look at Gear Change again. Published in 2020, it remains the most recent cycling and walking strategy for England, and it promised to “make England a great walking and cycling nation.” Five years on, I am keen to see how many of the promises made in Gear Change have actually been delivered. Given that it was a product of usefulness-challenged transport secretary Grant Shapps and the Boris Johnson government, we can probably make an educated guess. I would note only that after a one-year-on review of Gear Change, the government quietly stopped reporting on the lack of progress implementing it. ↩︎

Bibliography and Further Reading

Everything linked to in the text above.

Follow on Social Media

I’m not very active on the socials, but you’re welcome to follow me at…

Instagram: @the_beauty_of_transport

Bluesky: @thebeautyoftransport.com (or @danielhwright.bsky.social)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/thebeautyoftransport

Threads: @the_beauty_of_transport

At the very least, automatic notifications of new posts to this website should appear there.

Hope you don’t mind, but I’ve your blog a bit of a plug on LinkedIn here: Post | LinkedIn. You did challenge me a bit on this post, but that’s not a bad thing and I (mostly) see what you are saying here.

Great to have you back with more parkway madness! I mention you every time I pass through Havant… potty humour.

For the Southern Railway’s attempt to do the same thing i.e. place a halt on top of an embankment, the not-so-far-away Chestfield & Swalecliffe provide an interesting contrast. There’s no feeling of enclosure there, but after dark, it never feels the safest place to wait for a train.

From your photos the acoustic barriers on the platform feel like you’d be standing in a long row of garage doors! And why a dark grey? Looks rather oppressive. I can’t help but think a lighter, warmer colour, would have improved the look and feel of the place. Or something to break it up a little – even if it’s just posters.