Railway stations, bus stations and… filling stations?

The first two have made frequent appearances on the pages of this website, the third far less often. Filling stations, and their close cousins garages and car showrooms, only occasionally attract significant architectural attention. Although it can happen from time to time (there’s a list of filling stations that have featured here at the end of this article) most of them were built quickly and without particular thought to their appearance; certainly in more recent decades.

The early Twentieth Century saw more thought in general given to the appearance of garages. Even then, while larger garages, or ones in high-profile locations, might have been architecturally considered, many smaller ones had little identifiable architectural style at all, instead being essentially functional in appearance.

But no matter, because architectural photographer Philip Butler has a way of finding beauty in the mundane, as demonstrated in 226 Garages and Service Stations, his fascinating new book profiling Britain’s historic service stations and garages. And where garages did benefit from an architect’s hand, Butler captures the beauty and élan of the results. In short, British garages have never looked so good.

It felt like it was more than time for The Beauty of Transport to look at some non-railway design, and it has never featured an architectural photographer talking about their work before. So I was delighted to talk to Philip recently about 226 Garages and Service Stations, and understand the process by which he captures buildings and renders them by turn majestic, endearing, brooding or even – on occasion – hauntingly mysterious.

“It’s a collection of photographs documenting 226 different historic commercial garages from across Britain; some in use, some repurposed, and some derelict,” Philip says when I ask him to explain the overall concept of the book. The title pays tribute to Ed Ruscha’s seminal artist book Twentysix Gasoline Stations of 1963. Adding 200 garages to Ruscha’s figure must have taken some serious research work, not to mention the logistics of going out and photographing them all, I suggest. As Philip confirms, the book is the product of no less than six years of work travelling the length and breadth of the country.

“I started in 2019, and completed the work in early 2025, although I was also working on other projects during this time too. The covid lock-down also took the wind out my sails fairly early on, and probably set me back a year at least.” But Philip thinks the delay wasn’t entirely negative. “The time allowed me to develop the series better than it might have been in a shorter space of time, not to mention unearthing further examples.”

How does one go about finding photographically interesting garages and service stations, I ask. After all, I’m constantly surprising myself by stumbling across interesting railway stations, and they are generally considered quite well researched and catalogued.

“Unlike other projects I’ve worked on like Odeon cinemas or London tube stations, to my knowledge, old British garages haven’t been catalogued before,” says Philip. “Sure, some are listed buildings, but the majority of the locations were discovered by a combination of spending countless hours scouring online message boards, Google Maps, image searches and putting the word out on social media.”

Although old garages might seem a fairly niche subject (though, you know, that is what we specialise in here), Philip points out that transport architecture is far from the most overlooked genre of architectural photography. “If I’m honest, old garages probably draw more attention and appreciation than say, corner shops or sub-stations. When I first posted about the project on Twitter in 2019, I was inundated with suggestions, many of which I would never have known about otherwise. Even now, after the book is in print I’m learning of new ones that might have been up for consideration if I’d known about them earlier.”

I want to know what drives Philip to photograph buildings, and how he became an architectural photographer in the first place. “Taking pictures is always something I’ve felt compelled to do, whether it was with disposable 35mm cameras in my teens, SLR’s in my 20s or the digital equipment I use these days. I’m self taught, for better or worse!

“I’ve always been a bit of a collector, whether it be records, books or general objet d’art,” Philip continues. “When I developed a keen interest in photography, I found that I was also drawn to creating collections – in several cases, including this one, typologies of buildings. My interest in documenting architecture developed simultaneously with a love for inter-war ‘Art Deco’ design. A 1930s bus stop near my home was one of the first structures to draw my attention, and once I’d photographed that, I quickly started looking for more examples in the area to build a collection. It’s where my social media handle artdecomagpie comes from – I’m always looking for shiny jazz age buildings to add to my digital nest.”

226 Garages and Service Stations focusses on smaller, and less well-known buildings than the Tube stations or Odeon cinemas he has photographed for earlier books. “Garages appealed to me due to the wide range of architectural styles they present, and that the type of small rural establishments I generally focused on feels like a dying breed worth documenting,” Butler explains.

Philip’s detailed introduction to the book starts with a history of how “garage” (the word was added to the dictionary in 1902) evolved from meaning storage place for motor cars, to taking on additional meanings relating to car repair premises, which of course then also started selling fuel. This of course explains how ‘garage’ has become both the name of the structure attached to your house as well as the filling station or repair workshop down the road.

Philip then traces the evolution of British garage architecture, starting with the Art Nouveau Michelin House in Chelsea. The Mock Tudor and thatched cottage stylings of late 1920s garages were a response to the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act of 1928, which gave local authorities powers to dictate the appearance of new filling stations, the book explains. In the 1930s, many premises adopted Streamline Moderne architecture and after the war, concrete was used imaginatively to produce garages in forms which would have been impossible with pre-war methods. Eliot Noyes’ 1964 pattern for Mobil garages was the last time that there was significant architectural development of the form of garages, and Butler notes the, “homogenous appearance of rectangular canopies accompanied by standard box-like convenience stores,” which followed. Later architectural trends apparently largely passed the motor industry by, in Britain at least.

But Philip is also fascinated by smaller garages which had little in the way of architectural input. The “humble, purpose-built repair shops” of the 1930s are, he says, “equally as interesting and charming.” He has photographed many of these simple workshops with pitched roofs behind a stepped façade. “A nod towards Modernism, without all the fuss,” Butler notes. He also makes a connection between the introduction of the MOT for all cars over three years old, in 1967, and the huge rise in the number of building conversions to house car repair workshops after that date. Buildings as diverse as churches, cinemas, agricultural buildings, houses and an aircraft hangar all found second lives as car workshops, and examples of all these feature in the book.

Indeed, when I ask him if he has any particular favourites of the 226 subjects in the book, it is an example of a converted building he settles on. “I’ve got several, but the one that always makes me smile is St John’s Garage in Withorn, Scotland – a gothic church built in 1892, but converted into a garage and petrol station in the 1940s. It’s such an unexpected combination, and the bright yellow petrol kiosk contrasts beautifully against the stone of the building.”

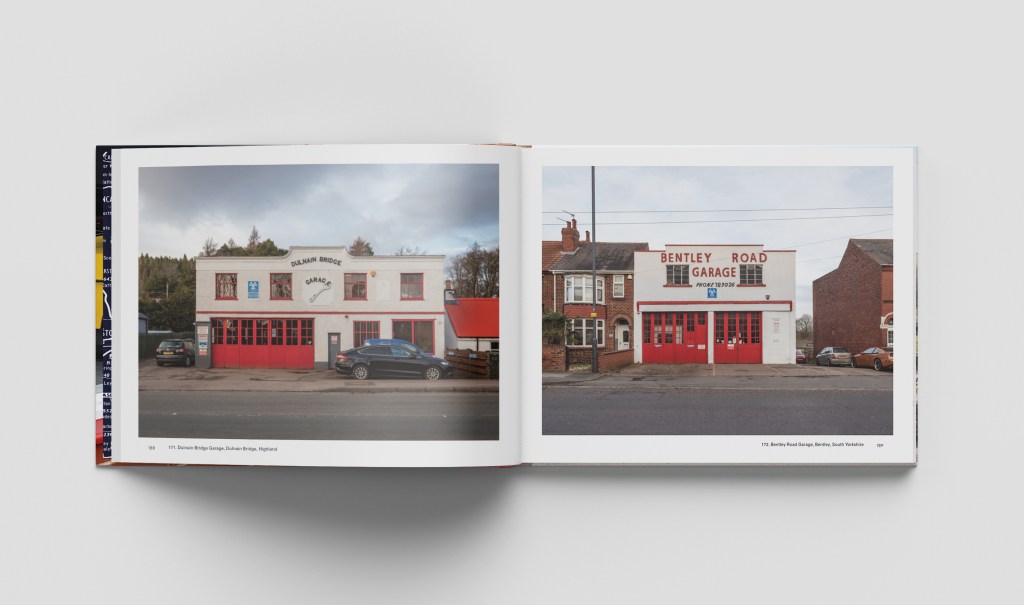

© Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

The organisation of the 226 premises in the book is delightfully considered, with pairs of buildings providing fascinating comparisons with one another, interspersed with the occasional double-page spread. “The sequencing of 226 was one of the most enjoyable elements of the project,” Philip confirms. “Again, I guess it goes back to the concept of a collection, and how you choose to display it. The garages are presented in a roughly chronological fashion, with each one partnered with a similar example. These are grouped by form or material or style, and the aim was to gently move from one group to the next. There was an awful lot of experimentation to try to make it work, not to mention specific road trips to complete certain pairs for the sequence.”

© Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

These site visits led to the odd unusual experience. “One time, the owner of a fairly unassuming garage invited me in to what turned out to be a private museum, packed with classic cars, old petrol pumps, motoring ephemera and two illuminated Compton cinema organs, all wired up to glow light Christmas trees, ” Philip recalls.

I am in awe of the work of architectural photographers, and their ability to capture not just the appearance but the essence of a building. Philip is ridiculously modest on this front, claiming “it’s probably one of the easiest types of photography!” To that, all I can suggest is that you might wish to compare Philip’s picture of Manor Road Garage, East Preston (below) with those I took for an earlier article about the same garage. Mine are OK, but Philip’s is exceptional. Like all his images it is imbued with an intangible magic that elevates it above the mere snapshots the rest of us take.

Hoping to uncover the secret of Philip’s magical photographs, I ask about his equipment and how he goes about deciding when to press the shutter button. “Usually, I have a digital SLR on a tripod with a wide angle tilt-shift lens,” he says. “I will have checked the position of the sun in relation to the location in advance, to ensure I arrive at the optimum time of day. Weather conditions are always a gamble, but that’s the nature of the game. I’m simply trying to take an honest image of the building that captures the structure successfully, nothing more than that,” he adds modestly. But he goes on to hint at the artistry involved too. “There’s always an element of fiction in a photo, the most notable example being a busy road. I only need a fraction of a second between cars to give the impression of a peaceful location, when in reality the opposite can often be true.”

With so much use of photo-editing software in contemporary photography, I ask Philip about his approach. “The question of post-production is a tricky one. Ideally I do very little, merely adjusting tones and shadows. However, the real world is messy. I have to make creative decisions on whether to use digital editing techniques to remove unwanted items from the images that obscure the building. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. Hopefully, you the viewer can’t tell which approach I’ve used from one image to the next!”

A number of the photographs in 226 Garages and Service Stations are taken just before or just after sunset or sunrise, and the lighting effects can be quite magical. Lighting conditions are an important consideration when curating photographs for a book, and the requirements can be different than when displaying photographs in other media. “I believe the preferred approach when capturing a series of similar subjects for exhibition is to have similar lighting so that the eye is drawn to the differences in the subjects. However, I produce work for books, and tend to feel a reader would lose interest in page after page of very similar photos. Offering a variety of weather and light hopefully helps break it up. I also love a bit of atmosphere, which low light helps with.

“Blue hour is the hour before sunrise and after sunset, there’s no direct sunlight, but there is still ambient light giving a sombre, sometimes eerie atmosphere,” Philip continues. “It’s less applicable to garages, but in the case of a neon clad cinema for example, I will often try to visit during blue hour.”

The remarkable Michelin House is shown at this time of day, and its resemblance, especially under these conditions, to an early Twentieth Century cinema is hard to ignore. Completed in 1911 to a design by Michelin engineer François Espinasse, it is finished in glazed terracotta tiles and topped by tyre-shaped glass cupolas which glow warmly in the twilight of Philip’s portrait.

In contrast, Philip says, “Golden hour is the hour directly after sunrise and before sunset, when the light, on a clear day, is quite literally golden,” Philip continues. “It can transform the appearance of a subject, adding an extra layer of interest to a photo.”

The Double-S Service Station in Ashton (Cornwall) is thus recast as a resident of a desert road in Arizona. The low angle and golden quality of the light brings out the detail in the rusting canopy support, granting it the appearance of a deliberate Corten steel structure.

I note that many garages in the book are derelict, but although some are, Philip cautions me to look more closely. “Sometimes, even the most rundown ramshackle buildings are still in daily use.” But in a world of supermarket filling stations and chains of repair shops, independent garages find it ever harder to survive. With the (slow, at least in the UK) move towards electric cars, filling stations in their traditional form face a challenging future. “I guess it’s sad, but I’m fairly philosophical about it. As a country we should be moving away from fossil fuel use, so the closure of an old petrol station isn’t really something to mourn. This aspect gives a sense of urgency to some of my projects though, as you never know how long some of these places will be around.”

With 226 Garages and Service Stations published, Philip probably deserves a rest, but isn’t taking one.

“My interest lies in inter-war modernist architecture in all its forms. I learnt fairly early on, that when travelling a significant distance to photograph a specific building for a book like this one, it’s wise to determine if there’s anything else on the route worth stopping for too. As a result, I’ve been simultaneously working on several projects at once. Suffice to say, there is another book nearing completion, which I will announce in due course.”

And he won’t say any more than that for now, at least publicly. However, I’m privy to further details, and I suspect it will greatly interest regular The Beauty of Transport readers. Knowing Philip it will undoubtedly feature delectable, and probably largely forgotten, buildings shown off in grand style. ■

- 226 Garages and Service Stations is published by Fuel on 4th September 2025 and is available to pre-order

With thanks to…

Philip Butler, for spending so long answering my questions about how architectural photography works, and generally putting up with me being a fan.

You can find Philip on Instagram and Threads, and at his website.

Other filling stations profiled on The Beauty of Transport

- Red Hill, Leicestershire, UK

- Markham Moor, Nottinghamshire, UK

- Helios House, Los Angeles, USA

- Nun’s Island, Montreal, Canada

- Frank Lloyd Wright filling stations, Cloquet and Buffalo, USA

- Repsol filling stations, Spain and Portugal

- Fina 2010 filling stations, Belgium and The Netherlands

Follow on Social Media

I’m not very active on the socials, but you’re welcome to follow me at…

Instagram: @the_beauty_of_transport

Bluesky: @thebeautyoftransport.com (or @danielhwright.bsky.social)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/thebeautyoftransport

Threads: @the_beauty_of_transport

At the very least, automatic notifications of new posts to this website should appear there.

One thought on “The Other Stations (226 Garages and Service Stations, by Philip Butler)”