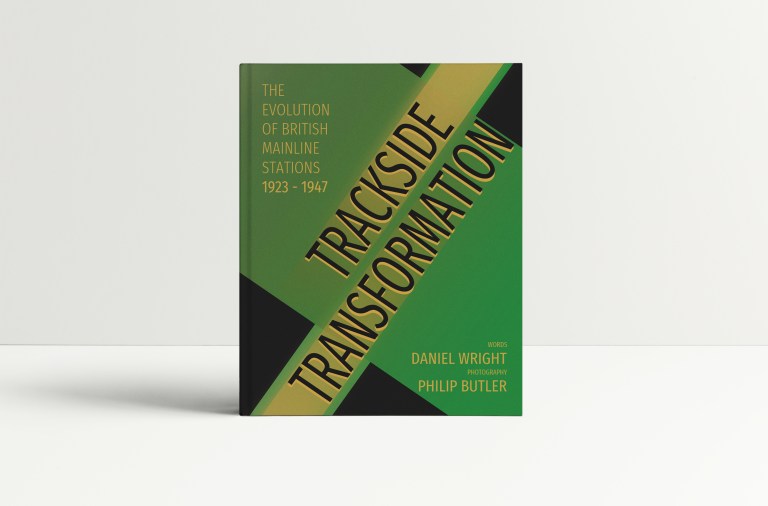

Have you ever had a project you’ve started on without any idea of the scale of work you’ve just committed to? Well, if you want to know one of the reasons that I haven’t been writing here as much as I might have done otherwise, I’m happy to announce one of the projects that has been keeping me busy. Trackside Transformation – the Evolution of British Mainline Stations 1923-1947 is due to be published in May – with your support.

Quite by accident, it might actually be the first book that has attempted to identify all the significant station architecture produced by the mainline railway companies of the Grouping era (GWR, LMS, LNER and Southern), and work out what survives and what has been lost.

Photographs © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

I was minding my own business quietly being an enthusiast for the buildings of Southern Railway chief architect James Robb Scott, when I was approached by architectural photographer Philip Butler in early 2023 with an intriguing request. You’ll know Philip from his recent and beautiful work on the architectural history of British filling stations. In 2023, and fresh off a book in which he photographed London Underground’s Holden-era stations, he was wondering whether there were enough surviving mainline stations from the Grouping era – which almost exactly coincides with the period during which Charles Holden’s London Underground stations were being built – to make a similar book possible.

If you like mainline railway station architecture from the 1920s, 30s and 40s as much as I do, you’ll understand exactly why I was instantly enthusiastic about the idea. We compared notes and came up with a list of about 75 survivors we knew about off the top of our heads. It’s a book I’ve wanted to own for ages but which no-one seems to have produced so far.

And then Philip asked whether, if he undertook the photography, I might like to research exactly which other stations had been built or rebuilt by the Big Four, and which ones survive, and write the text for the book.

I must admit that I assumed that someone else would already have collected together the information about the Big Four’s station building projects, and all I would have to do is copy out the names, pass them to Philip, and then get on with the writing. It was only once we started work that I realised that apparently, no-one had ever done this before. So rather than just finding some old book in the library at the National Railway Museum from which I could copy the list of stations and work out which ones survived, we actually had to try to identify the original estate ourselves, which was (to put it mildly) rather more work than we had originally expected.

Photographs © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

There are books about mainline railway architecture which cover the Grouping era as part of wider research. There are books which focus on the history of Big Four companies, but in which architecture is only one element. There are books which focus on the architecture of Big Four companies, but even these aren’t comprehensive, as we quickly discovered. But there is no book we have ever found which collects together the station architecture of all the Big Four companies, plus the ungrouped mainline railways, in a single volume. (If you are aware of such a book, at this point I think we’d almost rather not know.) Until now.

By the time we finished our research, we had identified over 280 stations built or rebuilt by the Big Four and the ungrouped railway companies. Some of these were rebuilt in conjunction with, or on behalf of, London Underground as part of that network’s extension schemes in the late 1930s. Although mainline stations at the time, they’re better known as Underground stations today, and have been comprehensively photographed for other books (including Philip’s). But even setting those stations to one side, we still had about 260 stations on the list, with just over 170 surviving to at least some extent.

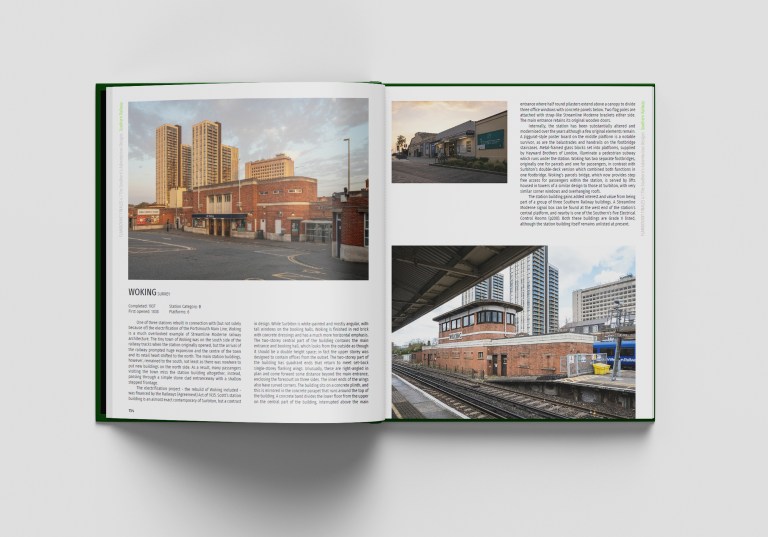

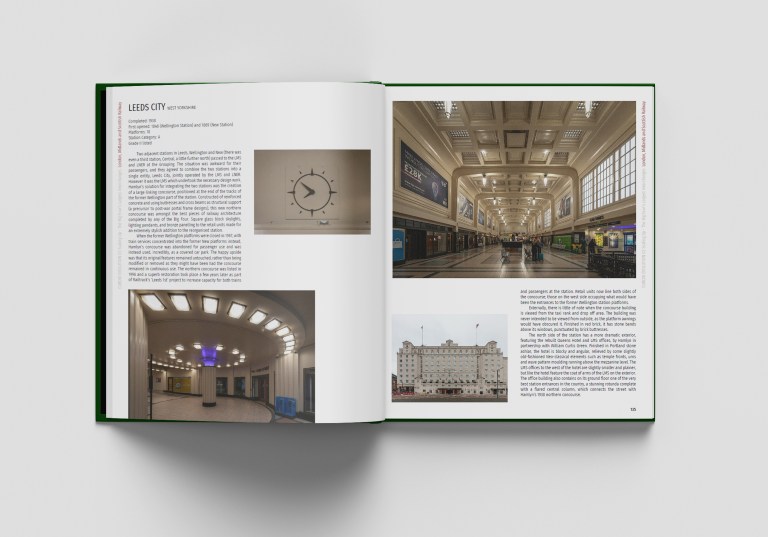

Some of them are quite well known, at least in railway architecture circles: Surbiton, Leamington Spa and Leeds, for instance.

Photograph from Trackside Transformation by Philip Butler and Daniel Wright © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

Others are much less so, like the delightful cottage-style Claverdon, Scunthorpe (who even guessed that was an LNER building?), South Kenton (I know it looks like an Underground station, but it really isn’t) and Feltham (best stair tower on the network IMHO).

Photograph from Trackside Transformation by Philip Butler and Daniel Wright © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

Trackside Transformation features Philip’s beautiful new photographs of every architecturally significant surviving mainline station from the Grouping period. It also includes some pages which collect together details of surviving but lesser works, or those which survive only partially or in heavily modified form.

We’ve also put in a range of archive photographs illustrating significant lost examples of stations from the period, of which there are an unfortunate number. And there’s an Appendix in the back which lists every single station built or rebuilt during the Grouping era, either by one of the Big Four or by one of the ungrouped mainline companies, which had significant architectural input. The Appendix even gives details of those joint projects with the London Underground. The only thing the book doesn’t include is stations – mostly halts – at which no significant architecture was provided. Even a few of the halts were graced with small buildings and those are in there too.

It’s a much more eclectic collection of buildings and building styles than London Underground’s stations of the same time period, so we’ve organised the stations into four sections, each covering a distinct architectural style. We start off by looking at Neo-classical stations like Margate, Cardiff and Clacton-on-Sea before illustrating the Big Four’s smaller stations, Domestic in scale and style. After that we’re onto the Modernist stations like Richmond, Doncaster, Leamington Spa and the Southend line stations at Chalkwell and Leigh-on-Sea. Finally – or at least that was the original plan – we move on to the Streamline Moderne and Expressionist stations like Surbiton, Horsham, Hoylake and Girvan.

Photograph from Trackside Transformation by Philip Butler and Daniel Wright © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

I say that was the original plan because Philip can’t help pointing his camera at inter-war buildings while he’s out and about, and I can’t resist writing about them when he shares the photos. So we’ve included a fifth section about the Big Four’s non-station architecture. It covers signal boxes, sub-stations, hotels and holiday camps, intermodal terminals, and shops (yes really), many of which are great pieces of Modernist/Art Deco design.

Writing pen portraits for the locations featured in the book made me wonder why the mainline railway network’s stations of the 1920s-40s seem to be so much less well-known than the Underground stations of the same period.

I suspect it’s for a number of reasons. While London Underground chief executive Frank Pick promoted the art, design and architecture of the Underground very publicly, the Big Four never really did. While Pick was talking up the tube stations of Charles Holden (and their architect), the Big Four regarded architecture as a subsidiary function of the chief engineer’s department. Their in-house architects never got the publicity that Holden did.

Another of Pick’s legacies was a culture at London Underground that appreciated the qualities of the architectural legacy of the inter-war Underground’s stations. While not perfect, the Underground has looked after the stations well, and they are easy to appreciate as design classics. It helps that the Underground has had a reasonably consistent ownership model in the years since the construction of Holden’s stations.

Photograph from London Tube Stations 1924–1961 by Philip Butler and Joshua Abbott © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

In contrast, the Big Four’s stations passed to British Railways at nationalisation of the network in 1948. Many were lost when stations were closed in the cuts of the Beeching era. Those that survived Beeching sometimes saw their buildings demolished in the cause of monetary savings. And the Big Four buildings that did survive were rarely maintained as well as their London Underground equivalents. Privatisation of the railway network in the 1990s didn’t help matters, with Railtrack (later Network Rail) owning the stations, and short-term train operators being responsible for day-to-day maintenance (or lack of it). It was under late and unlamented train operator Connex that the ceiling in the Southern Railway’s 1931 Hastings station octagonal booking hall was removed, such was its poor condition. The whole building eventually deteriorated so badly that demolition was felt to be the only option, and the whole station building was lost in 2004. This was a particular annoyance to me as I grew up Hastings and I used that station a lot. The new one just isn’t the same.

In fact, a great many of the Big Four’s stations have been very poorly treated by their subsequent owners, both public and private. Who would guess that under the utter mess which is Luton station today (boarded-up windows, rusting window frames, staining, horrible additions and extensions) there was once a stylish, Scandinavian-looking building built by the LMS in 1939? How did the Southern Railway’s Pokesdown, a super little suburban station in Bournemouth, get such terrible replacement doors and how did the lovely retail unit frontages (re-built as part of the station) end up looking so tatty and mis-matched?

Often, I suspect, when the public think of preserving heritage railway stations, they are mostly thinking of Victorian and Edwardian architecture, rather than Modernist stations from the 1930s. So the Big Four’s stations are often under threat today (in a way their London Underground cousins are not) partly because the public hasn’t quite got its head around the desirability of preserving post-Edwardian buildings. That has let the mainline railway sometimes get away with neglecting its estate of Grouping-era stations.

Photograph from Trackside Transformation by Philip Butler and Daniel Wright © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

Incredibly, Network Rail is involved in a scheme to demolish one of the very first Modernist stations on the mainline network – Wimbledon Chase of 1929 – and replace it with a block of flats. Given the state Wimbledon Chase has been allowed to get into (peeling paint, obscured skylights, vegetation growing out of the building), you can see why very few people locally have made much of a fuss, and planning permission has been granted. But it is feels highly unlikely that London Underground would entertain such a proposal at one of its Charles Holden stations of equivalent importance to the story of London Underground architecture.

There is hope, though. Sometimes the railway industry recognises what it has on its hands and gets round to restoration projects which undo the decades of neglect since the Big Four were swept away by the nationalisation of the railways. Such is the case at Richmond, which has recently been superbly restored, complete with Southern Railway-era glass signage discovered hiding under boards installed by British Railways. Doncaster benefitted from a similar scheme a few years earlier.

Photograph from Trackside Transformation by Philip Butler and Daniel Wright © Philip Butler, reproduced with permission

Sometimes the push comes from the community. Bishopstone station has seen much of its interior restored largely due to the efforts of Friends of Bishopstone station, which has nagged and badgered the railway industry to put resources into restoring the station, as well as successfully bidding for external match funding.

A common thread (indeed, common to Richmond, Doncaster and Bishopstone), as noted in Trackside Transformation, has been the involvement of the Railway Heritage Trust, not only by giving grants for restoration work, but also through providing advice, raising awareness of Grouping-era architecture as being just as valuable as that of earlier decades, and by gently leaning on a railway industry that can initially be reluctant to restore heritage features at stations.

Despite these rays of hope, the Big Four’s stations remain under-appreciated, sometimes under threat, and are rarely celebrated in the same way as inter-war London Underground stations.

We hope that Trackside Transformation will begin to change that. Study Philip’s photographs carefully and you can see the bones of high quality buildings hiding under messy accretions of signage and equipment, or boarded up and suffering from a lack of care and maintenance. And maybe the fact that those bones are so often so well hidden might just encourage Great British Railways to tidy a few more of them up. ■

How to get your copy of Trackside Transformation

Trackside Transformation will be published as a 216-page hardback. It is complete, proofread and ready to print, and it will be published via Philip’s ADM imprint. We think it’s important to support UK businesses, so we’re going to print in the UK on high quality FSC certified paper stock, but to do this, we need to raise some funds first. To support this, we have launched a Kickstarter crowd-funding page, which includes various exclusive rewards in addition to the book. There’s even an option for Philip and me to sign and personalise your copy before it’s posted out to you, if you want a more individual version. Although it’s only available at this stage to UK-based supporters, once it’s published in May it will be distributed through the regular channels; non-UK readers (hello!) should then be able to order through the main online retailers worldwide.

Kickstarter link (why not share with your friends?)

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/artdecomagpie/trackside-transformation

Subscribe to The Beauty of Transport

Enjoyed this post? Want to read more of the same without the hassle of checking the website for updates? Then enter your email below:

Follow on Social Media

I’m not very active on the socials, but you’re welcome to follow me at…

At the very least, automatic notifications of new posts to this website should appear there.

’Not because it is easy, but because we thought it would be easy’.

Best of luck with the book.

Thanks! We didn’t exactly think it would be easy, but we certainly didn’t realise quite how challenging the research phase would be. Glad we did it though.