It takes real talent to change the way an entire country looks, but that’s exactly what Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert achieved when they created the Transport typeface.

It’s everywhere on the roads of the UK, and a few other places too. It’s nigh-on impossible for a UK resident to avoid unless they never leave their house. It guides drivers from place to place unfussily and with extraordinary clarity, and some degree of friendliness. It has been designed to be easy to use, and is so successful that it’s mostly overlooked. In fact Transport is most often recognised in its absence, when an older road sign is encountered and you realise just how radical a change Transport represented.

A long time ago, we looked at the pre-1964 British Railways signage and its font, Gill Sans, an all-upper case work of art which gave train passengers strict instructions rather than friendly guidance. There was a contemporary equivalent on the roads, too. Designed by Llewellyn-Smith (possibly the civil servant Hubert Llewellyn-Smith although that’s not at all certain), no-one now seems able to say precisely what that typeface was called. It sometimes goes by the name Ministry (short for Ministry of Transport, the name of the government department at the time), and sometimes Llewellyn-Smith.

Ministry was used on what are now called “pre-Worboys” road signs; the reason for the name will become clear later. Some of them linger still on the roads of the UK, drawing attention to themselves because they are so clearly not written in Transport.

Gill Sans is all icy perfection, Ministry was less imperiously perfect but just as forceful and with a great deal of clipped style. Gill Sans was a work of art, designed by a true artist. Ministry, being for government, was perhaps always fated to be slightly less artistic. Mostly this stems from the fact it was more condensed: its letters were thinner so that an uppercase “O” was a tall oval, rather than a perfect circle as it would be in Gill Sans. Gill Sans was an ice maiden put to work in the service of the railways, Ministry was a bowler-hatted civil servant with a Savile Row pinstripe suit telling road users what the Establishment expected of them.

There are many similarities in the feel of the two typefaces. The razor-sharp corners on Ministry’s characters suggested that like British Railways’ use of Gill Sans, it wasn’t to be messed around with. Compliance (expeditious and uncomplaining) was the order of the day.

Signs in Ministry sat atop poles which were striped black and white, which was rather appropriate given the black and white times in which they were used, rather than the moral uncertainties and shades of grey in which we view instructions given from on high today. And just as you’d expect in a time when government and technocrats gave orders and the citizenry was expected to obey them unquestioningly, the typeface was displayed using only upper case letters. AS YOU’LL KNOW IF YOU GET AN EMAIL WRITTEN IN UPPER CASE, THAT MAKES THE MESSAGE YOU’RE READING LOOK VERY SHOUTY. Which was probably intentional.

![A pre-Worboys sign in Tolworth, London. This one has been preserved and restored. Note the lettering all in upper case, in the Ministry typeface, and the typical black and white pole. There's even a black and white strip along the top of the box giving the road number and destination. That indicates that the road is a trunk route. Photo by David Howard [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebeautyoftransport.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/pre-worboys_sign_tolworth_-_geograph-org-uk_-_1118930.jpg?w=768)

Today, coming across a Ministry-lettered sign on the roads is an unexpected pleasure. The typeface remains very stylish and now has the added benefit of accrued nostalgia for a more sharply styled past. The shock of reading an old speed limit sign in Ministry is enough to have you hitting the brakes of your car, so different is it to the feeling of reading one in the much less confrontational Transport typeface.

![Pre-Worboys 40mph speed limit sign in Bishop's Avenue. Photo by David Howard [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebeautyoftransport.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/450px-pre-worboys_speed_limit_bishops_avenue_-_geograph-org-uk_-_1324628.jpg?w=768)

Although widespread, Ministry wasn’t the only typeface in use on UK road signage before the 1960s. There were others in use as well, on “finger-post” signs, and on older road signs erected by motoring organisations dating from the days before government took on the job. Road signage was, in short, absolute chaos.

The opening of Britain’s first motorway was the straw that broke the camel’s back. An easily comprehensible and consistent typeface was needed for giving directions on motorways, as motorists prepared to whizz by signs at previously unimaginable speeds (assuming you drove a Jaguar rather than a Morris). A committee under the chairmanship of Sir Colin Anderson was formed to design the signage. Anderson employed designer Jock Kinneir, who brought with him a star student from Chelsea School of Art where Kinneir was a visiting lecturer, called Margaret Calvert.

The government asked them to produce a typeface for the signage which resembled contemporary German fonts like FF DIN. Like any designers worth their salt, they completely ignored this instruction and instead spent a long time designing the perfect font for getting across information in the fastest possible time with the smallest possible chance of misinterpretation.

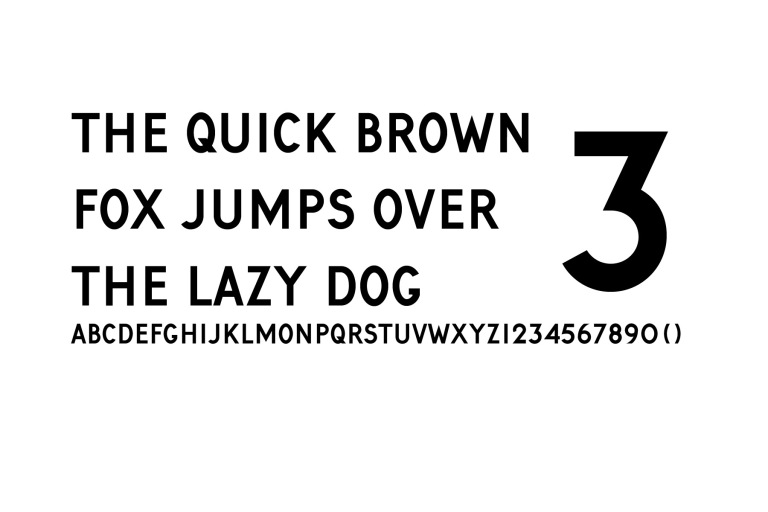

For a start, fractions were to have no dividing line (a small thing, but it helps the individual numbers stand out at a distance). Kinneir and Calvert drew inspiration from another transport typeface, London Transport’s Johnston, when it came to the lower case “l”, which had a small curve at the end, quickly differentiating it from an upper case “I” or a numeral “1” (unlike Gill Sans where all three were identical). By thinking about the most legible possible signage for British drivers, they invented Transport. Actually, they first invented Motorway, which is still the typeface used for the numerals, compass ordinals, and “A”s “Bs” and “M”s on motorway signage (it’s unusable as a font because it lacks the remaining letters in the alphabet), though Transport was used from the start for the mileage information and destination names on motorway road signs.

Kinneir and Calvert’s great insight was to realise that a lot of the time, drivers don’t really need to read the words on road signs at all. If they’re looking for a particular destination, they can pick up that information instantly from the shape of the word itself, rather than needing to actually read the letters making it up. But it only works if you use lower case lettering (with an upper case letter at the start). It’s the pattern of ascenders and descenders that gives a word its shape. If you use an all-upper case typeface as pre-Worboys signs did, the shape of a word is essentially a rectangle, and one is indistinguishable from any other.

![Roundabout sign near Edinburgh. Because letters are in upper and lower case, the shapes of words can be picked out easily. Photo by M J Richardson [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebeautyoftransport.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/bridges_and_roundabout_on_the_b701_-_geograph-org-uk_-_904646.jpg?w=768&h=576)

At least, that’s the generally accepted theory. But there was a battle to fight first. The Anderson Committee having sorted out signage on the motorway network, the subsequent Worboys Committee was set up by the government to standardise road signs on the rest of the non-motorway network (i.e. every other A, B, C, D and unclassified road maintained at public expense in the entire country…) Transport was the typeface it chose (it also sorted out all the standard pictograms we’re now familiar with, again designed by Calvert). Not everyone was impressed.

Designer David Kindersley had invented an alternative scheme for road signage which he thought showed that a typeface he had invented – MoT Serif – allowed for smaller road signs and was more legible, not to mention more suited to the English countryside. Such were the concerns of designers in the 1960s. Letters were exchanged in the letters pages of national newspapers – this was the latter-day equivalent of slapping your adversary around the face with a glove and calling them out onto a misty common to fight a duel. Research was quoted, and by all accounts frequently misquoted, to support arguments over which typeface was better. Legibility tests and experiments, which I have to say sound completely unscientific by today’s standards, gave somewhat mixed results, depending on assumptions made about the kind of sign you wanted in the first place.

But eventually Transport won through, and changed the face of the UK road network, and by extension the UK itself completely. Its clean, friendly-without-being-too-friendly characters are the perfect mix of persuasiveness and information propagation. For British people, there is something very British about Transport, even though most of them wouldn’t know what Transport was, nor why they recognised it if presented with the typeface out of context. An A-Road road sign, white Transport lettering on a green background, is as much a part of a drive through the British countryside as hedgerows, cottages, country pubs, duck ponds, cows, and the occasional 1960s microwave transmitter.

![As British as the British countryside. A modern road sign with Transport lettering. Photo by Ben Brooksbank [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebeautyoftransport.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/1024px-rushton_spencer_geograph-3503709-by-ben-brooksbank.jpg?w=768&h=487)

That said, British drivers in some rather surprising places can find themselves suddenly wondering if they’re back at home, because Transport is so obviously brilliant at what it does that it is used by several other countries on their road signs, too. It can be found as far afield as Italy, Iceland, Kuwait and India.

![A road sign in Kasaragod, India with Transport used for the Western lettering. By ARUNKUMAR P.R (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thebeautyoftransport.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/1024px-malkassignboard.jpg?w=768&h=576)

Transport was re-drawn and digitised by Calvert a couple of years ago and is now available for a much wider range of applications. Testament to its enduring Britishness is best found in its use as the font for www.gov.uk, the UK government’s central website, another example of something from the world of transport going rogue and infiltrating wider society.

As I said at the beginning of this entry, it takes real talent to change the way an entire country looks. The most remarkable thing about Kinneir and Calvert is that they did it not just once, but twice. Having transformed the appearance of the UK’s roads, their next target was the British railway network…

references and further reading

Garfield, Simon (2010): Just My Type. Profile Books: London

Department for Transport’s official diagrams for Transport, (see Alphabet drawings, here)

An article about pre- and post- Worboys signage, at cbrd.co.uk, here

More information about UK road signing than you can shake a stick at, at sabre-roads.org.uk, here

Transport and Ministry can be downloaded here, for personal use

Reblogged this on Recovering From Childhood and commented:

Transport is part of the UK ow – it says “UK” visually more than anything else, apart from the Union Flag I guess. Personally I always preferred the Rail alphabet the same designers produced for the erstwhile British Rail, but I have latterly come to admire the beauty of this typeface.

I too have had to do a double take on seeing the font used on foreign roadsides. Although the juxtaposition is real, it is a distinct reminder of home and allows you to settle in to your new surroundings.

It is a great font and this is a worthy article about it.

Thank you! Rail Alphabet is on the slate for next year – another font that went rogue from its British transport origins and turned up in some unlikely places.

As the name suggests, Transport was originally intended for a wider sphere than just road signs; before adoption of Rail Alphabet it saw limited use by BR for early 60s new builds – the illuminated white-on-black signs at Coventry station are a rare instance of this (the now-defunct signal boxes at Rugby and Bletchley also had some exterior signage in Transport), although for railway use block capitals were the order of the day.

Thank you for the comment; this was new information to me. There is an article on Rail Alphabet on the slate for later in the year, and I’ll see if I can track down a picture of any of the signage you mention.

The Southern Region (and possibly some of the other Regions) adopted the Transport alphabet briefly too. From memory, Dover Priory was resigned using the Transport alphabet in black on white. However, most of the Southern’s Transport alphabet signage was in white on green, such as the ‘totem’ signs at Seaford and Guildford (London Road). In the latter case, GUILDFORD was in capitals, whereas (London Road) was in lower case. At Twickenham, one of the green platform number signs (presumably a replacement) on the footbridge was in the Transport alphabet, with the other signs in Gill Sans and a darker shade of green!

“There’s even a black and white strip along the top of the box giving the road number and destination. That indicates that the road is a trunk route.”

Nope. The black-and-white strip indicates that the turn-off is a link road to the road number indicated. Modern signs use brackets instead. So the equivalent post-Worboys sign would give the destination first and read “Leatherhead (A 243)”.

Thank you – I stand corrected. I’m beginning to realise that the pre-Worboys signs were more complicated than I thought. I have altered the article accordingly.

On a recent trip to Lisbon my brain found it hard to accept that the speed limit signs where in kilometres and not miles. If I’m not mistaken this is another country using Transport! I would love to be confirmed or corrected 🙂

As a British expat living in France it certainly felt surreal going to the outer reaches of Europe and getting such a strong reminder of home!

Thank you for this post which obviously stuck in my memory from when I first read it a long time ago.

Yes, you are quite right. Portugal does use Transport on its roadsigns. And if you’re used to mph speed limit signs, then the kph ones do look really strange.